Testing stereotypes through physical comedy

by Lu Donovan

“HONEY, huhhhhney, Rose isn’t coming.”

Complete with full costume changes and faux video interviews, Rose Luardo transforms into five different personas in her solo performance Pedestrian Circus. This is the final show in Almanac Dance Circus Theatre’s Miniball Festival, and Luardo opens the piece as a provocative agent from LA, interrupting the usher’s pre-show introduction by making flirtatious advances at them. She continues, hitting on audience members, and I try to settle into the bombasity while desperately hoping she doesn’t reach my row.

This first character refers to Rose in third person, handing out Rose’s business cards as she reminds us that she won’t be joining tonight. I remember this distancing throughout the piece as Luardo puts on the outfits, personalities, and lifestyles of her other characters, her clowns. In my brief Lecoq training with Emmanuelle Delpech through the Headlong Performance Institute, I came to understand clowning as an acting method through which one’s most childlike, vulnerable, and authentic self can shine through the guise of “another.”

Luardo’s “others” are a horny southern woman in her 60s, a washed-up English guitar tech, a flouncy gen-Z party influencer, and a whining philanthropic woman from Gladwyne, PA. Though each individual is distinct, themes of drug use and hypersexuality remain as Luardo makes cliches of her characters. None of them are likable. The entire audience cackles at every joke. Each persona is grating and offensive.

Richard Pimm, the English guitar tech, talks about his cocaine-infused days and the irreversible changes his body endured from drug use. Pimm pulls down his jeans to reveal his 3-foot-long flaccid cock with matted pubes. The dick is a hand-sewn stuffed stocking, supposedly nothing more than a soft sculpture. He waddles over to the front row and “accidentally” grazes people with his cock, allowing it to fall into the laps of audience members.

What’s the assumption at play that makes it okay for a woman to touch people with her dick? What are the agreements between performer and spectator that allows for this, and when did we shake hands on them?

Casual body shaming sputters around, there are side comments discounting queer pronouns, and one character perpetuates violent anti-Asian rhetoric about coronavirus. As folks around me howl and hoot, I’m drawn into the dissonance between my understanding of clowning–a portrayal of the most authentic self–and Luardo’s opening line, “Rose isn’t coming.” If so, then who is responsible for these jokes?

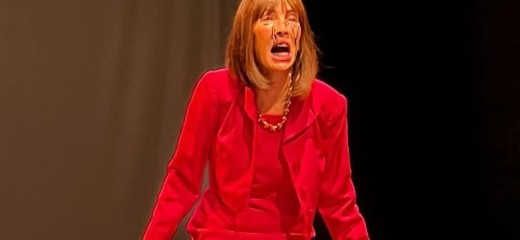

Struggling to find humor, I turn toward Luardo’s movement choices for inspiration. Each outfit change provides an opportunity for Luardo to hold herself in a new way. In a loose turtleneck, silky trousers and loafers, the southern woman walks with an eager perk, slowed only slightly by age. Dressed in heavy denim from head to toe, the English man takes crouched strides with a grounded bounce. Sporting platform crocs, tight pleather pants and a sheer crop top, the young party influencer swings her limbs with abandon. However, it was only through the last character, the “good woman” from the Main Line clad in a Talbots dress, blazer, and pumps, that the physicality not only bolstered the personality, but also offered a clear critique and message of the persona herself.

Her tight skirt forces her ankles into a lady-like cross and the 5-inch heels mandate teeny, dainty steps. The structure and restriction of the costume informs the character, a rich suburbanite who fits into every role a “good woman” should be. Reacting to a Change.org petition against her business idea for “infant shapewear,” she begins to tantrum. She breaks down and wails, transforming her body from its vertical stature to a puddle of jigsawed limbs. Her knees knock toward each other as she crumbles to the ground. Her shoulder pads slide off her collarbone as she holds her torso on wavering elbows. She’s in complete physical desperation, made more obvious by her outfit’s constriction, and the dissonant embodiment feels like I finally receive a signal that Luardo is, in fact, playing with satire.

It’s true, I’m not versed in comedy as an art form, many of Luardo’s punchlines depend on cultural references outside my generation, and my sense of humor generally falls outside the rash style portrayed in Pedestrian Circus. Yet, I’m still left with my reaction of discomfort, disappointment, and questions for the artist. What is Luardo’s responsibility, as a comedian, creator, and performer, to contextualize the offensive social and political comments she hollers? I was left awaiting a brief trick, a momentary lapse in character, where Luardo signals to her audience that she’s critiquing these beliefs. With the exception of her last character, the characters arrive, throw themselves around the stage, and depart without awareness or analysis of their positionality. Is the form of comedy itself that “wink, wink” I’m looking for? Does humor absolve responsibility for perpetuating harmful ideals?

Pedestrian Circus, Rose Luardo, Christ Church, Philadelphia, Miniball Festival 2022, Dec. 17-18

Image description: A character in a bright pink dress-suit faces the audience with black tears streaming down her face. Her knees buckle inward and her hands flail out in despair.

By Lu Donovan

January 8, 2023