Theatre Philadelphia and thINKingDANCE continue our partnership, begun in 2018, bringing coverage and new perspectives to Philadelphia’s vibrant theatre scene.

It was giving family that Friday night at the Community Education Center (CEC) in West Philly. A large, extended family made up of ebony-elbowed elders, arms outstretched to all, strolling past a stall with jewelry for sale, and a pale yet-ever-present feeling that we are here to witness a truthing, a truth-telling, a non-lie.

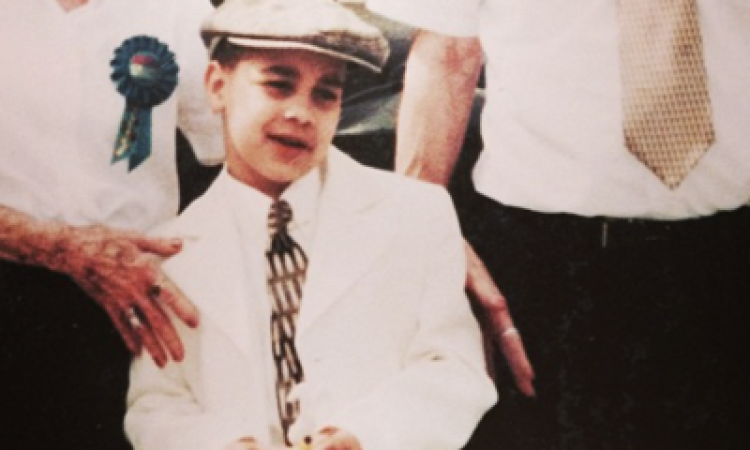

Carter Ford’s Lessons from an incomplete black boy, presented by Producer’s Guild and directed by Vanessa Ogbuehi, is an intimate, one-man reenactment / reflection on the playwright’s experience growing up as a biracial, paler-skinned boy in a world determined to simultaneously define and misunderstand him. The work is punctuated softly, reflectively by the trumpeter in the corner, part of a trio of jazz musicians who fill the second half of the show.

Dressed in a blue-green flannel shirt and jeans–the sort of outfit someone’s dad might wear to their kid’s grade-school show–a kindly white man introduces the show. Mr. Ford, as we come to know him, introduces his son’s work with the misty-eyed fullness of a parent wholly aware of his son’s courage. He acknowledges the outpouring of support from Carter’s mother and the church family that fills the audience. Carter takes the stage and immediately transports us to all-too-familiar and awkward places: school, the neighborhood, and spaces filled with kids unlike him, molded by adults very much unlike him as well.

A game between the kids becomes tense when the kids egg-on Carter to do something dangerous. “You know what Carter, don’t be what my dad calls you…” says a white playmate to Carter.

“Well…what does your dad call me…?”

Ford hones in on the us/them and then there’s me dynamic of being biracial by playing back scenes from our own lives, through his lens. Grown men use the “n” word to deter young Carter from playing at a park. A prospective girl crush, although Black herself, doesn’t see the teenage mixed boy as one of her own, but the epitome of why she “doesn’t date white guys.” We’ve all been there, right? I wonder how many reading this can say that.

An especially poignant moment happens at his grandfather’s Irish wake lineup, where Carter is assumed to be unrelated to the other mourners. Carter recalled the sting of an attendee’s “entitled skepticism.” After having to swear that his grandfather was the one in the coffin, after having to admit that he wasn’t given his father’s and grandfather’s name (as is tradition), after fleeing to the bathroom to wet and therefore straighten his hair…young Carter has to “be the bigger person” by paying no mind to the woman who couldn’t fathom his ancestry.

Pay no mind, bigger person… those trite, saccharine, bandaid-when-you-need-a-suture sayings we cling to in order to preserve our much sought-after peace. These sayings get bandied about by well-meaning family–allies who, although related, can never fully relate to not being able to freely inhabit the miracle of being alive in a biracial body.

Never fully relate to not being able to hang out with all the other Black boys (lest you threaten them with your light skin) or hang out with the white boys (lest you threaten them with your dark skin) or be aware of your Blackness (but don’t “talk white” lest you forget your place and how much privilege you are given) or just be at peace (although you will be called the “n” word, and cracker, mulatto, zebra, gumbo, fake).

Pay her no mind though, because you’re better. Carter poses a question to us at the end of this spiraling eddy, one that I’m familiar with deeply. The question is: “Am I better? If I’m supposed to pay these people no mind, these people who seem to have community, then…why am I here?”

“Is it still bad to call you people gumbo?”

The adjective “incomplete” fits this piece aptly, not because of any lack in its writing or production, but because of the main character’s experiences as he tries his damndest to navigate the black/white binary world around him. At each stage he finds gaping chasms between what other people think they understand about people like him, and what he knows to be true about himself.

“Incomplete” because of the way white delusion finds ever more twisted ways to delineate who is whole and who is half, and what those people are allowed to do, and how they are supposed to take up space, or not. Incomplete because the role of “educator of the masses on all things race” is not a paid position, but somehow, bi/multiracial folks of all complexions and features have to educate, train, and HR their way through all camps. In Carter’s words, “being constantly bullied out of race groups only to not be accepted by the group” you’ve been…kicked into.

Gerrymandering isn’t just on a map. It’s in the geography of the cafeteria and the playground. It’s in the topography of the bar or club space, the adult cafeteria/playground, where the same, achingly tense presentations and reports on race and what it means to be biracial are reenacted, as if none of us have learned anything in this swift growing-up we’ve had to do. A growing-up that’s thoroughly incomplete.

Lessons from an incomplete black boy, Producer’s Guild, Community Education Center, April 8.

To join the conversation, follow thINKingDANCE and Theatre Philadelphia online and on social media to read, share, and comment.