The Grand Union—They Were Their Own Material

by Leslie Bush

“Impulse is extremely seductive,” says Barbara Dilley in an interview for The Grand Union: Accidental Anarchists of Downtown Dance, 1970-1976. Flipping back through my copy of choreographer, and dancer Wendy Perron’s rich narrative of the performance group, I notice stream of consciousness notes scribbled in random pathways through the pages. Perron’s account of the six years that the group worked together excites an attention to my own impulsivity, the same “awake and ready to respond” feeling she remembers when she saw the Grand Union perform.

The Grand Union traces the history of the eponymous dance improvisation group, from its preformation influences in and around the Judson Dance Theater of the 60s, through its eventual disbandment. Revolutionary in their approach to movement, the motley crew created “something out of nothing” during their more than fifty performances as a collective. Perron relies on archival footage, interviews with group members, reviews, and her personal memories to puzzle together a full picture of the ensemble—cheekily named the Grand Union after a chain of supermarkets—whose primary members were Barbara Dilley, Douglas Dunn, David Gordon, Steve Paxton, Nancy Lewis, Yvonne Rainer and Trisha Brown (1936-2017) with whom Perron danced. Interludes from other artists and writers at the end of each chapter broaden the Grand Union canon further.

The opening section of the book sets up the unique mix of circumstances that led the troupe together, rooted firmly by early trailblazers like Anna Halprin and John Cage, and by Rainer’s Continuous Project--Altered Daily. The anticapitalism and anarchism of the SoHo artist community in the late 60’s and early 70’s was also crucially influential. Perron is careful, though, to contextualize SoHo as an artistic utopia for “white, young Americans.” Throughout the book, she recognizes other communities with considerably more diversity who were equally active in experimental performance practices; a standout interlude from Dianne McIntyre considers the impact of her Sounds in Motion company in mid-town and Harlem contributing to the proliferation of dance improvisation.

Emphasizing both the collective sensibilities and the individuality of the members, Perron delivers a nuanced and comprehensive account of the history and impact of the group. She dedicates the second section to exploring each of the seven performing artists (plus a chapter on Lincoln Scott and Becky Arnold, who were members for a short time). Her thoughtful profiles focus on individual backgrounds and physical performance styles. I enjoy these short descriptive portraits; it’s a gift to know these titans of postmodern dance on a more intimate level and they lend context to the motivation and dynamics of the collective.

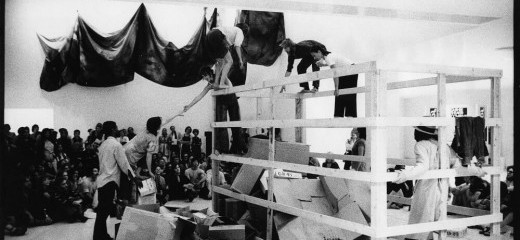

The Grand Union was decidedly leaderless—although Perron frequently calls into question what “leaderless” meant—and in most of their improvisations, there was no plan. They relied on pure chance. The book describes some of Grand Union’s performances and residencies, recounting Perron’s perception of events from archival footage. She is not dogmatic in her interpretation saying that she “shaped the unfoldings according to my own sense of cause and effect.” Her descriptions serve to capture the unique and implicit process that the group collectively—and spontaneously—had in a performance. Task based movement, talking about what they were doing while doing it, and play were the tools with which they rebelled against any preconceived notion of dance. The descriptions are generous and exciting; she captures a kinetic flow that tumbles with momentum from one scene to the next.

One intriguing conversation is about identity, an idea teased out over several sections. What part of the performers’ “selves” did the audience see? It points to the uncovering of process in the Grand Union improvisations, the real life tension between players which would spill out into the space. But she also is quick to deny that the troupe was always fully themselves; this is an oversimplification in her eyes. For the Grand Union members this debate misses the point; in reading their interviews and Perron’s renderings of their performances, I’m inclined to agree. The ethos of this ensemble disintegrated rigid boundaries. Both/and/or/neither were all things that could exist in the same time and space. This pithy summation puts it best: “they were their own material.”

Their “own material” was the behind the scenes lives that they led collectively and individually. They sometimes struggled with each other, with being on tour with children, and with their own artistic endeavors. A moment of extreme vulnerability comes in an interview with members about the impact of Rainer’s suicide attempt in 1971. It’s a profound reflection of how connected they were. Hurt and anger began to play out onstage; arguments were some of their favorite bits to improvise. In the end, the magic that brought them together, began to break them down. “Anarchy doesn’t last forever,” the group disbanded after six years.

The Grand Union: Accidental Anarchists of Downtown Dance is a deeply impactful book for the historical dance canon, overflowing with rich detail. It is a beautiful account of a group whose influence collectively and individually extends outward into the greater contemporary dance ecosystem. There is a timeliness to their story, read in 2020: art and life inextricably linked. I find myself wondering, how would a Grand Union performance look now, in a moment where our homes are our workplaces, our creative spaces, our stages? What of their process would be revealed?

Wendy Perron, The Grand Union: Accidental Anarchists of Downtown Dance, 1970-1976 (Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 2020).

*Related Reading Lisa Kraus, David Gordon’s The Philadelphia Matter 1972 / 2020 in the FringeArts Festival of 2020. Gordon’s The Matter originally was a project of Grand Union.

*Wendy Perron speaks with thINKingDANCE

By Leslie Bush

December 10, 2020