Dance, Reanimated on the Page

by Emma Cohen

“Matters of materiality, and its spirit. These things matter to me. Matter matters” (p. 9).

In Drawing the Surface of Dance: A Biography in Charts, Annie-B Parson is deeply attuned to the vibrancy of the material world. Though much of her choreographic work is structurally oriented and abstracted, she is equally concerned with, as the title of her opening essay would have it, “stuff.” Collecting drawings, collages, photographs, and texts that pay close attention to the details of materiality, Drawing the Surface of Dance weaves the detritus of past performances into a newly generative artifact. Designed by Standard Issue, the careful construction of the book itself underscores Parson’s preoccupation with meaning-laden and aesthetically precise objects.

Within the dance world, Annie-B Parson is perhaps best known as the director of Big Dance Theater, where she has choreographed and co-created performances since 1991. But her work is not restricted to the realm of concert dance: Parson has created choreography for operas and movies, as well as for musical icons David Bowie, St. Vincent, and David Byrne. These varied contexts are collapsed, to exciting effect, in Drawing the Surface of Dance, where performances from across all realms of Parson’s career comingle.

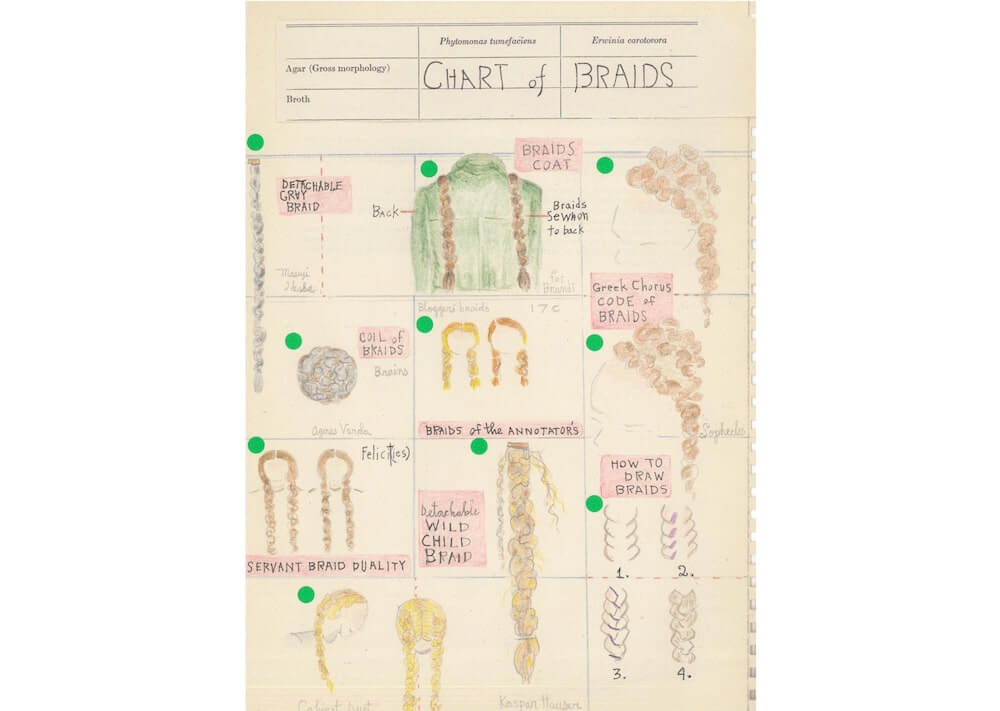

In the first section of the book, “Charts of Works,” Parson presents collages that she created in the aftermath of her dances. Ordered chronologically and accompanied by short but illuminating pieces of text, these charts track the substance of each performance through its material components. Props, costumes, and set pieces are sketched in loose lines and bright colors, occasionally layered over fragments of text. Often the connections between objects are mysterious (what are a parasol, a carnation, a fur shawl, and “Satan’s dirty feet” doing together?) but this opacity allows for the reader’s own fantasies to unfurl across the page.

Prefigured by Parson’s opening essay, in which she reflects on newfound through-lines in her work, motifs that recur across charts quickly begin to emerge. Braids and mustaches appear again and again, as do rolling chairs and sticks. I thought tape was only present in Here Lies Love, then found it again in Lazarus. In their calls and echoes, these objects refuse to calcify into clear symbols. Instead, their meanings multiply and reverse, folding and expanding in response to one another.

Photo: Ike Edeani

Photo: Ike Edeani

These associative networks become more explicit in the book’s second section, “Structures and Scores.” In addition to providing insight into Parson’s choreographic processes, these charts show attention to broad themes and recurring imagery. Here, every stick that has appeared in Parson’s work is gathered onto one page, as are all things circular—both props and gestures placed side by side. As Siobhan Burke writes in her insightful closing essay, “through her etchings and collages, Parson teases out the web of relations among our living, corporeal beings and the objects in our midst, honoring how we all move through the world together, interdependently” (p. 171).

The third section may at first appear to be the most straightforwardly documentary portion of Drawing the Surface of Dance. Titled simply “Big Dance Theater in Photos,” it includes images from throughout Big Dance Theater’s history. And yet even here the relationship between past performances and their current indices remains dynamic. Certain images reach backward into the pre-performance research process: a photograph from 17c zooms in on a dancer’s hand sloping gently downward in front of a navy silk shirt, while an image across the page crops Frans Hals’ painting Portrait of a Lady to frame a hand held at the same angle in front of a navy bodice. Later, a photo from a 2011 performance reaches forward to an image from 2017: though clad in different costumes, the dancer in each image pitches her weight forward in the performance of what appears to be the same movement.

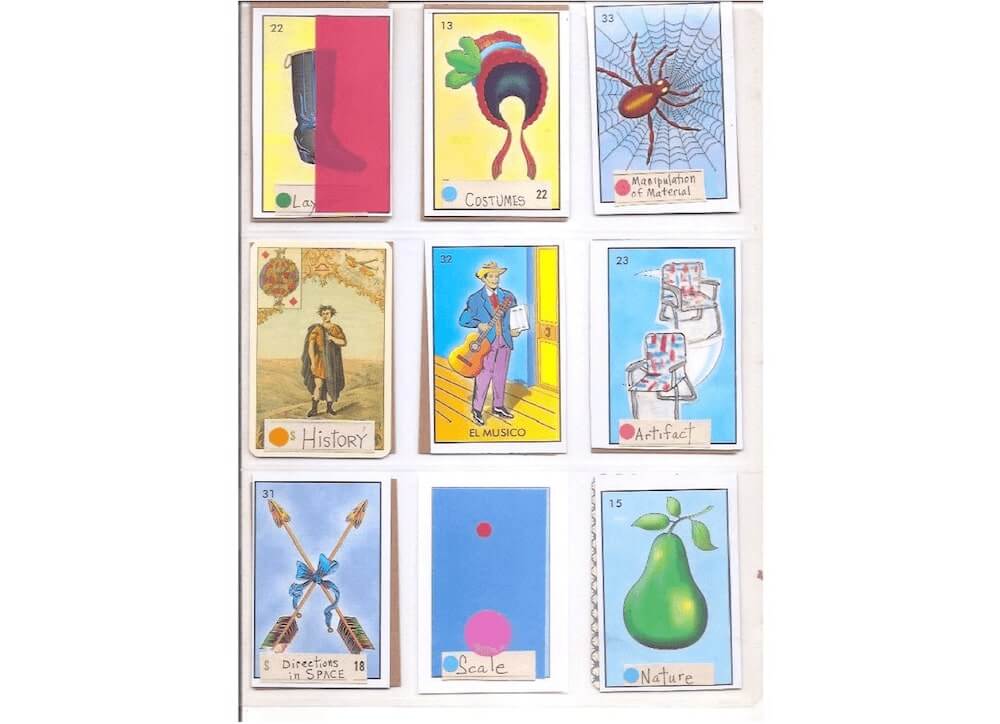

While Drawing the Surface of Dance does serve to document Parson’s choreographic oeuvre, it harbors more expansive aims than those of many dance archives. There is no attempt to lay out meticulous notes so that works could be precisely restaged in the future, nor do these charts endeavor to recreate the experience of seeing the works live. Even though Parson writes that "choreography is more perishable than dancing, and dance is more perishable than fruit” (p. 8), she doesn’t seem to be operating from fear of dance’s ephemerality. Instead, fragmentary images and concepts are brought together so that they can continue to flourish and develop in a new environment. This invitation to bring Parson’s work into new contexts is proffered quite literally in the fourth section, where cards bearing compositional elements and prompts can be cut out and used in dance-making. I was thrilled at the prospect of taking a book apart and bringing its pieces into my own life, even if I was ultimately too skittish to cut the book’s glossy pages.

Photo: Ike Edeani

Photo: Ike Edeani

Parson’s evocative sketches and thought-provoking scores go beyond the lineage of dance notation that abstracts a dancer’s gestures into lines or maps bodies’ movements through space. Rather, I am reminded of the drawings Trisha Brown created in her performances of It’s a Draw; Drawing the Surface of Dance is a similar sort of debris that retains the traces of a previous performance, while also becoming an autonomous art object.

The final page of the book contains a dry list of photography credits and copyright information. Yet I was tickled to find, in the bottom corner, a small photograph of a woman lying supine on the floor, her short grey hair curling out from underneath a party hat. With no context for the image, I was filled with questions and imagined narratives—a past performance was newly activated by my gaze. For a project concerned with the afterlife of dance and the vitality of objects, it seemed appropriate that the content of the book would overflow its typical boundaries, that the dance would find a way to sneak back in.

Annie-B Parson, Drawing the Surface of Dance: A Biography in Charts. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2019. 175 pp.

By Emma Cohen

November 23, 2019