I think not, I think not, I think not

By Becca Weber

Just as our minds integrate the same information in different ways, so too, do our bodies. But are these individual interpretations still, at their core, the same thing? The Deborah Hay Solo Festival raised this question as it presented three distinct versions of the same dance. Each was created during Hay’s Solo Performance Commissioning Project, an 11-day residency where artists commissioned Hay to coach them through a solo improvisational structure. Performers committed to at least three months of daily practice before presenting the work. In Hay’s process, “scores” are filled in by the dancer or executor of the solo. Each score adaptation is unique, revealing something of the performers themselves, as well as communal, sharing a framework.This shared individuality was highlighted by Friday’s triple bill, all adaptations of Hay’s 2011 work, I Think Not. Chairs circled the performance area, creating a sense of inclusiveness and intimacy. Hay’s opening words contextualized the show. She is interested in how the dance is performed, rather than what the body can do. She also identified her greater goal to enlarge the experience of dance so that it includes the audience, space, time passing, and an attention to the whole body as the teacher.

The performances began with Nicole Bindler’s rendition, which emerged slowly and grew into a fidgeting, awkward, crouched tango. Throughout her dance, the extremities, especially fingers and toes, were emphasized as the point of initiation of gestures and traveling sequences. The flesh of her fingers and toes was highlighted by their exposure in her costume of purple short-alls. Her gaze was steadfastly transfixed on the eyes watching her. Moving beyond the stage and back again, all limbs and digits, she shifted her focus to her right hand: “Roger,” She named it. She named her left “Tamera.” Her vocalization emerged as a resounding, reverberating tone. She galloped, bounced, wound and unwound as the nonsense lyrics of an indecipherable lullaby escaped her mouth. She lay down, still with heavy breath. Then eventually, as she rose, her song continued. She looked into the audiences’ eyes. And then she was gone—having exited through a back door, her song slowly drifting away.

In this first piece, I had not yet been able to discern the structure. But that changed with Manfred Fischbeck’s adaptation. Dressed in black, seated amongst the audience, he began his dance by looking around like an inquisitive viewer. Then blackout. Lights up: Fischbeck was already dancing in his chair. He rose and advanced, bouncing with limbs extended. His exploration grew into roundness, curving in on himself, until he reached one of three small sculptures of interwoven circles. He lifted it and wore it as a hat; it wiggled on his head as he feigned a sword fight. He played an invisible violin. “John,” he whispered, with his right hand holding the “bow.” “Elizabeth,” he said to his left. Ah-ha! I recognized this. After Fischbeck laid down, his deep breathing hastened as he began a mumbled song. Donning the other two sculptures on his arms, he then handed them off to audience members. His dance concluded, much the same as it began, in his seat amid the spectators.

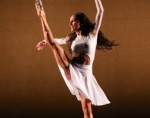

Sally Doughty entered upstage, her long chiffon tutu, sparkled black tunic, and feathered fascinator headband nearly upstaging her. Gazing at the audience, she fiddled with her skirt. Gazelle-like, her long arms billowed around her head as her skirt swallowed her uneven footsteps. “Now I see it,” she stated, as her foot peeked out from under her costume, “Now I don’t” as she slipped it back underneath. She crouched, her tutu enveloping herself: “Now you don’t.” Moments later, the now-anticipated naming of her hands (“Bill” and “Miriam”) had arrived. She crossed the space, in a dance of perpetual falling and graceful port-de-bras, floating atop an arrhythmic, gangly gait. Her nonsense song began. She lay down, her belly rose and fell quickly…Yes! Just as the others before her! She stood up, sang her own gibberish song, stared into the audience’s eyes before exiting exactly as she entered.

In the end, the highlight of the evening was discovering the universal structure of the dance. Viewing these three performances together gave a glimpse of the individuals’ input into their separate processes with Hay. The variations on the nonsense song were intriguing. Through the similar-but-different moments, clues—but not a full explanation—were given. I wondered about the names they chose to designate their hands. Were they perhaps their parents’ names? Why “I think not”? I may never know. Ultimately, these unanswered questions point to another question Hay put forth at the start: “Is adaptation a viable form of transmitting dance?”

I Think Not, Deborah Hay Solo Festival, Nicole Bindler, Manfred Fischbeck, and Sally Doughty. thefidget space (in partnership with Mascher Space Cooperative), November 9.

By Becca Weber

November 28, 2012

.png)