Dance as an Exploration of Love, Pain, and Performance

by Caitlin Green

Penn Live Arts’ An Evening of Short Dance Films featured three works that distinctively honored the art of movement. The films accentuated dance as a utility for translating personal and collective stories. As a hip-hop lover, Nicholas Brothers: Stormy Weather (2022) stuck out to me as most captivating. The film creatively embedded a historical moment into the current performance culture, paying homage by connecting past and present.

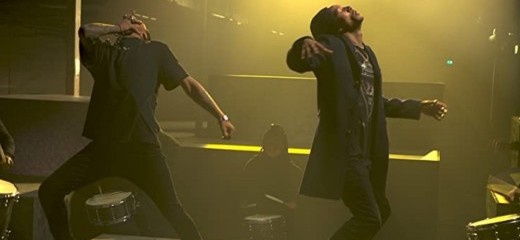

Directed by Michael Shevloff and Paul Crowder, the documentary is a tribute to the prolific tap performance duo whose impact would continue to inspire dance through the decades. The film time-travels between 1940s Harlem and 20th-century London, using black-and-white archival footage of the Nicholas Brothers (Fayard and Harold Nicholas), along with present-day captures of Les Twins (Laurent and Larry Bourgeois). Les Twins carry on the Nicholas Brothers’ legacy through deep study blended with a contemporary spin on hip-hop dance. By combining the percussive elements of tap dance, smooth, sweeping qualities of jazz, and the high-energy aerial partnering present in lindy hop, the Nicholas Brothers wowed audiences with their busy choreography and magnetic chemistry. Their style included a wealth of adventurous jumps and acrobatics as they experimented with the body’s limits of balance, flexibility, and stamina. This would become inspiration for the subsequent arrival of breaking—a major staple of hip-hop that surfaced decades later, and it became a pulse for today’s performance artists Les Twins.

More than their trailblazing talent, the Nicholas Brothers represented the poise of performance. In a general sense, yes, but even more as Black men in the ‘40s, whose routines were often hosted at venues like the Cotton Club in Harlem, which denied entry to people of color. Les Twins consider what it must have entailed to summon the mental and emotional fortitude of such a venture. One in which humanity and talent are dichotomized in terms of value, and that value determined, in this case, by the white gaze. How did they arrive on stage in costume decorated with glowing smiles and undeniably gleeful personas among these conditions? One of the Bourgeois brothers wears a contemplative expression before he decidedly concludes, “life made them dance like that.”

We Dance (2022), a narrative directed by Ethan Payne and Brian Foster, is a three-part love story. In the first two segments, a woman and man share a reflective account of their upbringing. Guided by poetic voiceovers and a gentle melody, the film’s motifs illustrate the formative details in the dancers’ biographies. Watching the film felt like the motion-picture equivalent of flipping through an old photo album. Sweet potatoes and pound cake are prepared in the kitchen among other unwritten cooking rituals carried out by the grandmothers who nurture them. Serene nature scenes are grounds for dance in each person’s story: a forest with a stream passing through, the sun peeking over a lake at twilight. The dancers’ movement seems organic like their surroundings, following an inner impulse rather than concerning a particular aesthetic, genre, or technique.

In the third account, two memoirs become one. They speak a monologue in unison and a duet emerges from their solos. Their arms curve around one another in an enamored embrace. Unlike the other screenings, dance wasn’t the main focus of this film; it was a byproduct of love and an agent of connection and intimacy. There was a familiarity in the lovers’ movements, seemingly derived from a recipe cultivated from ingredients as complementary as the butter and eggs in their grandmothers’ pound cakes. It was a visual poem. Though the predictability of the narrative made it plateau for me, its stunning graphics accompanied the rhythmically recited words and illuminated their symbolism in an artful work.

Downstage (2020) by Stephanie Owens outlines the challenges and accomplishments 11-year-old Aeden faces while embodying elegance and grace through the postured and hyper-disciplined practice of ballet. Despite the strength required to accomplish the technical rigor of the dance, Aeden quickly learns it’s not the type of strength that validates social norms alluded to masculinity. As a brown boy, he brings a unique identity to an environment that values uniformity on the basis of European, feminine beauty standards. He speaks on the emotional and physical challenges packaged in the pursuit of becoming a professional ballet dancer.

The film shared several glimpses of intimacy between Aeden and his mother, and I gained a sense of assurance. The nurturing guidance counteracted the strain of ballet’s physical and social training, especially as an outlier in the industry during his formative years. Together Aeden and his mother indulged in private moments of embrace, laughter, and play which were among the few lighthearted moments of the documentary. The choice to include such tender exchanges amidst the more tumultuous accounts of the lifestyle added a softness to the documentary.

I left the event reminded how much dance exists dually as agent and recipient of our social worlds. Dance can be a valuable tool for testing the limits of our minds and bodies, whether it be through ebbs and flows of creating and dismantling self-esteem, discovering deeply synergetic connections between two or more people, or paying homage to the greats by passing on their gifts of inspiration. Each film reflects the body’s astounding capacity to explore and thrive in dance.

An Evening of Short Dance Films, Penn Live Arts, January 19.

By Caitlin Green

January 26, 2023

.png)